Military Jeeps, Campus raids, Flourishing student culture, 70s Makerere in the Lenses of the Late Gen. Elly Tumwine.

Communications Department

Mak@100 Secretariat

“We carried Gongom back to the School of Fine Arts together with Kibiira, who was the best at metal welding and reconstructed a bigger Gongom. After some time, we sculptured gongomess to keep Gongom company. How the name Gongom came about, I don’t know.”

“I can tell you we really had a good time, except for the bad times of Amin in 1976,” says Gen. Tumwine opening the pages of his book, Liberated, as he settles down to tell the story of his time at Makerere University during the tumultuous period of the 1970s Uganda.

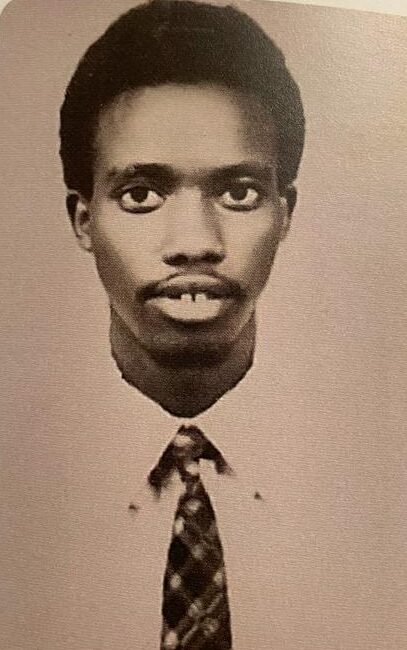

Born in Burunga, modern-day Kazo district, then part of greater Mbarara, Gen. Elly Tumwine attended Mbarara high school for his O’ level and St. Henry’s Kitovu for his A‘ level studies. He enrolled at Makerere University in 1974 to study Bachelor of Arts in Fine Art which he pursued concurrently with a diploma in Education.

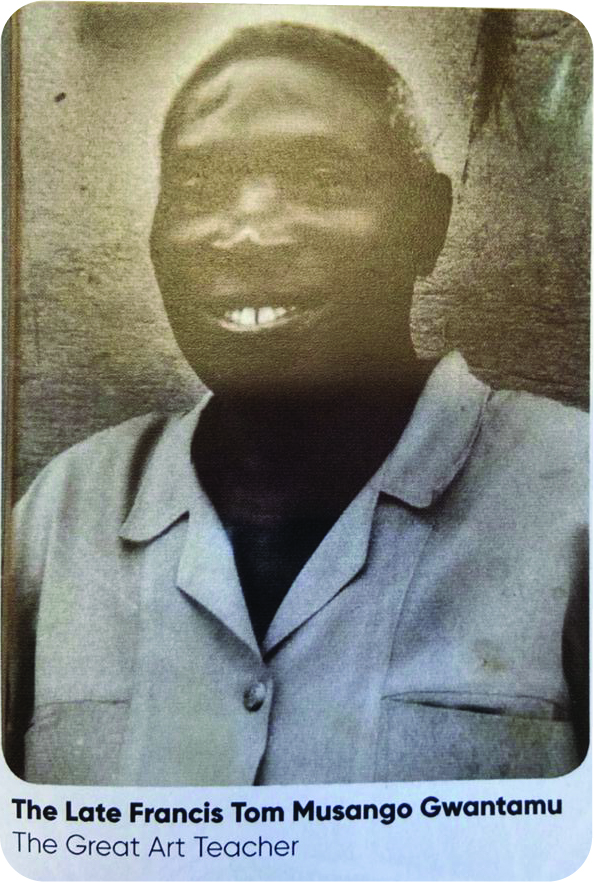

Gen. Elly Tumwine says that his love for art started way back in his senior one at Mbarara High school when he met his art teacher, Mr Rock Ruganza, an artist and guitarist, who would occasionally play at White Nile, a Nankulabye-based club in Kampala. It was Ruganza who initiated him into the craft and also guided him to take it as a principal subject for his A’ level studies at St. Henry’s Kitovu, in Masaka. It was here that met the man that would have the most impact on his art career.

“I wanted to be a lawyer like my two Cousins; John Wycliff Kazoora and Grace Ibingira, until Mr. Francis Musango Gwantamu, made a joke that when you’re an artist, you don’t need to look for a job,” Gen. Tumwine says.

After the classes, he went to the teachers’ quarters to inquire from Mr. Musango Gwantamu about more details on a career in Art. Gen. Tumwine says that he found him painting, and he explained to him that Art was a career of passion and freedom as evidenced by his pastime activity of painting that he was enjoying very much after a day of teaching.

From this moment onwards, Gen. Tumwine became determined to pursue Art at Makerere University, a feat he achieved when he enrolled at the Margaret Trowell School of Industrial and Fine Arts in 1974.

Life At Makerere

Gen. Tumwine joined the Margaret Trowell School of Fine Arts at Makerere University in 1974. He says that by that time, it was the only advanced school in the whole of East Africa that was teaching Fine Arts.

Having joined Makerere as an orphan, and his year of enrollment coinciding with Amin’s policy of banning the student allowance, then known as boom, Gen Tumwine insists that his art life at Makerere was the most exciting time of his youth.

“My art life at Makerere was the most exciting time of my youth, when you are young, you have an opportunity to go into the field, to live with nature. And I think that’s the best opportunity you can have. Most people don’t know the universe.” he says, “I was liberated by the mind. With art, you are liberated to free your mind, and look at things with an objective view. You are shown how to capture moments.”

As an orphan at Makerere in the Amin years of scarcity, Gen. Tumwine ventured into photography to make ends meet. It was here that Art came in contact with passion. He says that he acquired an Olympus PEN camera which he would carry around the campus in the evenings after lectures capturing, ‘benching’ couples and students’ events. “I was rich on campus, even richer than today compared with my current responsibilities,” he says. “Between 5 and 7 in the evening, he would finish two to three films. “ I had a briefcase full of negatives.”

This ingenuity, he says, pushed him to become the first person to introduce express photography at Makerere University, teaming up with three other students from his School of Fine Arts, they first attempted their craft at the boxers event in the main hall (Boxer to mean Mary Stuart Hall)

“I was the first to introduce express photography, and it began with the boxers event in the main hall. Together with three students of art. We divided ourselves, one would be taking photos, one in the backroom and another one setting up. By the time the Boxers finished, we had their photos ready.” Gen. Tumwine says. He adds that this event became an eye-opener and later they started shooting sports events and other functions at the university which were able to generate enough income for their survival at the university.

But if that was the height of his ingenuity in Art School, the golden opportunity would later present itself in 1975 as Uganda prepared to host the Organization of African Unity (OAU) Heads of State Summit at Nakivubo in Kampala. The Department of Fine Arts had been tasked by the government to design books that would be used at the conference, a job they had been working on, but this time the government wanted something else: the portrait of Idi Amin to be displayed at Nakivubo.

The Lecturers had shunned the responsibility, pushing the project to students. Four students from the newly formed Makerere Fine Art Students Association were selected to draw the portrait. Gen. Tumwine was the secretary-general of the Association. He recalls, “Soldiers would bring Amin’s picture in the morning, guard it, and take it back in the evening.” After days of intense drawing, a 16 by 10 meters drawing was presented by the students to the Ministry of Education.

“We were paid 1.4 million shillings. The four of us. The Painting is still in the Ministry of education.” Recalls Gen. Tumwine, smiling. “It was my first time opening a bank account.”

Gen. Tumwine explains that it was years spent at the Makerere school of fine art that widened his eyes to appreciate different interpretations of the world and that they were the most fundamental in the transformation of his life into the man that he turned out to be.

“The art world is a different world. There is nothing more liberating than you having the freedom and means to create what is not there, and without you feeling bad; There are two categories of people in this world; those who create what is not there, and those who just follow what category number one has created.” Gen.Tumwine says, further noting, “That is the beauty of art, and that is what I am saying that my years at Makerere were most fundamental in transforming the rest of my life; my thinking, my philosophy, my joy…”

Black Tuesday, Gongom, Gongomess

The year is 1976. It was five years into the Amin government, and so far the relationship between Makerere and the government had not been cosy. The atrocious and repressive activities of Amin’s soldiers and State Research Bureau Agents, followed by the government’s cutting of student allowances had planted the seed of mistrust and hatred between the University student community and the government.

The events that preceded the Black Tuesday of 3rd august 1976 were; the death of Vice-Chancellor Frank Kalimuzo in Oct 1972; the banning of NUSU in 1972; the banning of the Guild in 1973 following Guild President Otunu’s flight into exile after he had ostracised Amin; the removal of student pocket money allowance (boom); the Feb 15th disappearance of Kenyan Student Esther Chesire; the Paul Sserwanga murder; and the brutal murder of Mrs Nanziri, the warden Africa Hall, among other incidents.

Gen. Tumwine recalls, “what spoiled our time at Makerere was a difficult time. Then there were shortages. People were bringing cassava at the gate. Those who had attended Makerere in the previous years had eaten like lords, eating butter. During our time we used to line up for every single commodity.”

Following the murder of the Law student Sserwanga, just near the entrance of the University hall, Makerere students decided to demonstrate. His murder had happened just weeks after the abduction and death of Kenyan student Esther Chesire. The government was refusing to take up the responsibility, twisting statements that the shot person was a runaway thief in Wandegeya. Gen. Tumwine says that they were organized by Kagata Namiti, then chairperson of Lumumba hall to meet in the freedom square in the morning and march to Kibuli, Serwanga’s home for burial.

“We marched to Kibuli when they killed Serwanga at the gate of University hall. We put on our red gowns and marched through Kampala road, with Amin’s State Research Bureau standing on each side of the road. I really can’t count. We were many and we marched from Makerere up to Wandegeya. The procession was huge. Then we went up to Kibuli and buried.” He says.

Students had caught the government unaware, and on their way back things turned messy. General Tumwine vividly remembers, “as we were burying there, the military police Commander organized jeeps from Makindye and drove them up to the hill. So as we were coming downhill, they came to crush us, we scattered in all directions, but returned to the university jovial.”

The demonstrations forced Amin to appoint a Commission of Inquiry to look into Serwanga’s death with Makerere Geography department Professor Langlands as Chairman and Elly Karuhanga, then State Attorney in the Ministry of Justice as Secretary. The Commission began a listening visitation to students in their halls of residence, but Professor Langlands was arrested by SRB and accused of inciting students against the government during his rounds. He was summarily deported from the country.

The decision only served to further anger the students, and as Byaruhanga records in his book, Student Power in Africa’s Higher Education: The Case of Makerere University, the students tabled their demands: that the vice-chancellor makes a statement on President Amin’s demand that the university provides the names of the purported anti-government students; that the student guild and boom must be reinstated; and that food diet should be greatly improved, among other things. Failure to do so would lead to lecture boycotts and mass demonstrations.

Byaruhanga further records, quoting Guweddeko that on the morning of August 3rd, 1976, the D-day of Black Tuesday, students moved towards the university main gate at about 11:00 a.m. The troops, commanded by Brig. Taban Lupaayi and Major Minawa (both Sudanese) Lt. Col. Itabuka and Kasim Obura charged from two sides shooting in the air. Some frightened students fled, while those who took cover, military-style, were arrested. But the real horror of the day was to come in the night.

As Gen. Tumwine recalls, “In the middle of the night, the soldiers were banging doors everywhere, taking us out and parading us, starting from Mary Stuart and Lumumba. Because we were the biggest and noisiest halls.” He says that he was able to escape the torture by hiding in the wardrobe inside his room in Lumumba Block C 316. It was later reported that girls in Mary Stuart hall were sexually harassed and some raped, while boys were made to move on their bare knees from Lumumba to St. Augustine Church while being beaten with gun butts.

General Tumwine says that although he doesn’t know the origins of the word Gongom, its symbolic significance began on the night of Black Tuesday. He recalls that one Fine Art Student called Kibiira had welded a small metal sculpture during inter-hall competitions, which was then placed at the entrance of the Lumumba hall. During the night of the raid, soldiers vandalised and destroyed it to pieces, the following morning, students went looking for metals to reconstruct Gongom, now as a symbol for protection.

“We carried Gongom back to the School of Fine Arts together with Kibiira, who was the best at metal welding and reconstructed a bigger Gongom. After some time, we sculptured gongomess to keep Gongom company. How the name Gongom came about I don’t know.” Gen. Tumwine says.

Appeal to Makerere.

General Tumwine notes that Uganda’s history is not well documented and is full of gaps and that Makerere should be at the forefront of correcting wrong narratives, and documenting history such that it should be taught to future generations, like the Americans.

“America had a program on the radio in the 1960s called ‘The Making of a Nation,’ and we used to listen to it daily. They narrated their history, liberation, and independence. It was consistent.” He says. “My greatest appeal, especially using these hundred years, is that Makerere is the greatest institution that should write the history of Uganda. Uganda is not properly documented. And its proper history should be taught in all schools so that it doesn’t disappear.”

You can access the video recording of this interview here

Get Involved

Are you a Member of Staff, Student Body, Alumni, General Public, or Well-wisher? Find out how you can get involved here, or share your Makerere experience with us.

Makerere

Makerere