A dance at State House, sharing a class with male students, East Africa’s first woman medical doctor tells her Makerere story

“When I joined University, many people in my village wondered whether I, a girl they had watched growing up, would make it. At that moment, though, they were in a frenzy having already heard the news,”

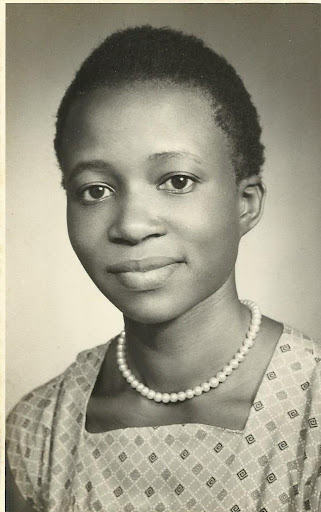

Prof. Namboze Josephine was the first female medical student of Makerere. Raised in Nsambya, now a Kampala suburb, Prof. Namboze’s visits to Nsambya Hospital, in the early years of her life, inspired her to become a medical doctor. Prof. Namboze recollects that her parents would take her and her siblings to the Hospital, nearby, for treatment whenever they fell sick.

During her tender years, before she learnt to speak English, her father, Joseph Lule, then a well-known teacher based at Nsambya Teachers Training Centre (TTC) would interact with the doctors. It was from those visits that she got the inspiration to pursue a medical career, a feat she achieved in February 1959, becoming the first female medical doctor in Eastern Africa when she graduated with a Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery.

Back then, it was called a Licentiate but had the same status as a Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery, she says because on graduating, they would apply to join the British Medical Council. Graduates with the Licentiate were entitled to practice medicine in Britain and throughout the British Commonwealth countries.

“When I went to Britain,” she explains. “We had exactly the same status as the other doctors there. After Makerere University College became a constituent of the University of East Africa, our qualification became Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery.”

Prof. Namboze’s education journey started at home, doing household chores and interacting with her mother, a housewife. And seeing Makerere students speak English during childhood left her with a deep sense of inspiration. Late on Sunday mornings, Prof Namboze would hide in the banana plantation to make herself invisible while she watched the congregation from St. Peter’s Nsambya Cathedral disperse. Among them were grown-up boys that went to school at Makerere.

They lived not far away from Prof. Namboze parent’s home and spoke English most of the time, a language she did not know. “Their older brother, who had also been to Makerere, owned the only car in the village at the time,” Prof. Namboze says. “On Sundays, they attended church in their uniforms- Khaki shorts, white shirts and green blazers with the Makerere badge. Afterwards, they proudly walked along the village road. Everyone eyed them with admiration and their smart uniforms carried immense prestige.”

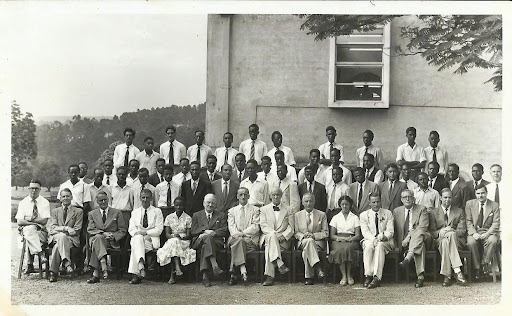

From learning, Prof Namboze joined St. Joseph’s Primary School Nsambya. She then joined Mount St. Mary’s College Namagunga and thereafter, Namilyango College from 1945-50. She was the first woman admitted to the Faculty of Science at Makerere University College of the University of London, in 1951, to study Higher Sciences, which in the current education system is equivalent to Advanced Level.

Joining Medical School was highly competitive and the intake was small. Only a handful of aspiring students from East Africa made it. “I studied physics, chemistry and biology,” she says, referring to the two years of Higher Sciences at Makerere University College where all her peers were male students. When she sat the final exam, she passed highly and received an academic prize, which came with money. The Medical School accepted her application. “With that prize money, I bought my first book in Anatomy,” she says.

At that time, female students stayed in what is currently Makerere University Guest House. “It had the feel of a boutique hotel. Our beds were made for us, the bed linens were sparkling white, changed regularly, and our rooms cleaned daily. Each room had two to three women students with a private bath. Meals were hotel standard,” she recollects.

Just like in the Faculty of Science, she was the first and only female student in her class at the Medical School. Other women joined in successive intakes, before and soon after she graduated. They were Dr. Apolonia Lobo (Braganza) from Kenya, Dr. Rosemary Bagenda (Koinange) from Uganda, and Dr. Satuant Singh from Tanzania.

Medical School was intense, Prof. Namboze says, and it was hard work throughout. “You had to exert yourself to the maximum and sacrifice all other interests. There were frequent tests—written, practicals and orals called viva/vivae—and we had to pass each and everyone,” she says.

“Unlike other students, we had four terms and rarely had academic breaks. We, the female medical students, and by that time we were just two, stayed in Mary Stuart Hall by ourselves, with the Custodian and Resident Tutor, while the rest doing other courses went home on break, including the cooks. We had to prepare our own meals. But school was also enjoyable,” Prof. Namboze says.

All the students were treated the same, and the same standards were expected of them, she says. “We had to be punctual on the dot, and to dress smartly for the classroom and ward rounds.”

But Prof. Namboze says two members of the teaching faculty were women. They were Dr. Margaret Stanier, who lectured in Physiology, and Dr. Carolee. W. Rendle-Short, a Professor and Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and a Fellow of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

As Prof. Namboze entered medical school, Mary Stuart Hall, the first hall for female students, had just been completed. Females moved from Makerere Guest House and occupied it. She would walk four times a day between Makerere Hill and Mulago to attend lectures. She had to set out early enough in the morning to make it to the lectures by 8:00 a.m.

As time went on, a friend, Ursula Musoke, who was a Fine Art student, offered to lend Prof. Namboze her bicycle, a gift from her father. Given that she didn’t know how to ride, she turned down the offer. But later on, the walk to Mulago seemed to get longer, prompting Prof. Namboze to start taking riding lessons. A time came for her to garner enough courage to take up the offer after learning how to ride. “I left Mary Stuart Hall riding her bike and prepared for the people that would gape in silent wonder in a culture where women were not supposed to do such outrageous things,” she says.

Prof. Namboze further reminisces; “as I approached Makerere College School, I could not get the bicycle to halt. That was when I realised the brakes did not work. Rather than veer into the main road and risk a car knocking me, I quickly opted to swerve and bump into a nearby tree so the bicycle could come to a halt. I returned it immediately, without blemish. Nor was I injured. Never again did I attempt to bike, to this day. ”

Prof. Namboze says her friend Ursula had been in the habit of lending out the bicycle to many friends and was unaware of the malfunction. She warned her not to dare ride the bicycle until it was fixed.

The lunch hour required walking back to Mary Stuart Hall on Makerere Hill through Wandegeya, a bustling trading centre where many knew her regular walks, and then quickly back to Mulago for afternoon classes that started at 2:00 pm. “That was really a rush hour. I had to walk hastily under the strong midday sun but I managed because I had a goal to pursue,” she says.

Prof. Namboze says members of faculty at the Medical School, notably Dr. Jack Davies, a Professor of Pathology, offered her rides, every after the day’s classes. They would drop her by the Tennis Courts on the way to their homes elsewhere on campus, which was extremely kind. That was close enough for Prof. Namboze to walk a few steps to Mary Stuart Hall.

Other notable personalities who used to offer Prof. Namboze rides in their luxurious cars to the Medical School included Mr. Serwano Kulubya, the first African Mayor of Kampala, whose daughter worked in the Dean’s Office and Hon. Chief Serwano Kigozi, the Kangawo of Bulemeezi County .They gave me words of encouragement,” she says.

Prof Namboze says the Katikkiro (1950-55) of Buganda Hon. Paulo Neil Kavuma took a personal interest in monitoring her progress from the time she was still at Namagunga. At the time, Kavuma was the Ssaza chief of Kyaggwe County, where the school is located. “When he visited, we sang for him, danced and recited poems. My poems made him laugh and requested encores,” she says. “That was how he got to know my name. As Katikkiro, he was pleasantly surprised to hear the small girl he knew from Kyaggwe had joined the University. He gave me his unwavering support.”

A few years after Prof. Namboze’s graduation, Galloway House, located on Mulago Hill was constructed and named after Professor Alexander Galloway, who was a long-serving Dean of the Medical School from 1947 to 1962. “Unlike other faculty members in our time, he was chauffeur-driven due to his status,” she says.

Medical students started having their lunches at Galloway House, from then on, and only walked once from Makerere in the morning, and then back to their halls of residence in the evenings.

The red undergraduate students’ gown was in existence during Prof. Namboze’s time at Makerere. Students donned the gown during official ceremonies and also to access dinner in the dining hall. “We had to put on the gown to identify ourselves and confirm that we were residents of Mary Stuart Hall,” she says.

Ms. Margaret Graham, the Warden of Mary Stuart Hall for many years, was extremely supportive of the women students and often invited them to dine with her at the High Table, and on some occasions, with her guests, who were prominent people in society. Students freely interacted with the Warden’s guests from countries such as the USA, Britain among others, who travelled to Uganda to assess the standard of women’s education in the country.

“After dinner at the High Table, she invited us for coffee and to listen to the BBC radio newscasts in her house attached to our hostel so we would be conversant with global affairs,” Prof. Namboze recalls. “That was part of our informal education,” she adds.

Ms. Graham liked meeting parents of female students whom she invited to lunch or tea, at least once, so they would know their daughters were in good hands. For a while, Prof. Namboze says she ignored Ms Graham’s requests to meet her parents, hoping she would forget, but she kept insisting. “My parents came, worried that maybe something was wrong, only to find a hospitable lady that had prepared a special tea for them. They had a nice visit,” she says.

The Warden also taught etiquette on how women ought to carry themselves as students at the university and later, as graduates. “She taught us that people looked at Makerere University students as the leaders of tomorrow,” Prof. Namboze says. “We had to carry ourselves with dignity, dress well and interact with respect,” she adds. When Ms. Graham left, after we had moved to Mary Stuart Hall she was replaced by Ms. Ann Burnett. She inspired Mary Stuart Hall residents to take a keen interest in looking after flowers and plants just as she did. Ms. Hannah Stanton replaced Ms. Burnett and carried on the role of stewardship of university women.

Attending a State House dance

A wife of one of the lecturers from Britain conducted free recreational dance lessons on the veranda and grounds of the Main Building overlooking the Faculty of Agriculture every Monday evening, for interested students. And many social events at the university would climax with a dance in the Main Hall. Female students at Makerere were few and so, other females were invited for the dance from institutions around Kampala, Prof. Namboze remembers.

Guest performers from other countries held concerts at Makerere, Prof. Namboze says, among them, Louis Armstrong Satchmo, the celebrated American Jazz musician, and his All Stars troupe, while on an overseas trip in May 1956. “I watched him live from the front row of the Main Hall gallery.” She says.

On some occasions, the Governor of Uganda, Sir Andrew Cohen, attended events at Makerere Main Hall and joined students in the dance. Governor Cohen had a great interest in financing and promoting the advancement of higher education in Uganda.

Once, he invited university students to the State House in Entebbe for dinner and a dance afterwards in the State House gardens. “We travelled in style in three minibus coaches. I was lucky to be among those who went,” Prof. Namboze recalls. “We had to be carefully selected. If you were not sure of your dance steps, you wouldn’t be a candidate” she says.

Prof. Namboze had perfected her ballroom dance steps in Rumba, Samba, Waltz, Slow Foxtrot, among others from the dancing lessons both at the university and while at Namagunga, where she and a dance partner won the Annual Inter-school award for European dance.

Prof. Namboze started taking dance lessons while in secondary school. Towards the end, Ms. Catherine Senkatuuka, one of the first female students admitted to Makerere University College in 1945, then an Education student was on teaching practice at Namagunga. She taught students Ballroom dancing as part of recreation. “Ms. Senkatuuka also told us about life at Makerere,” Prof. Namboze remembers, “since we all aspired to go there.”

A Moment of Jubilation

In December of 1958, Prof. Namboze went to hide as far away as possible at a friend’s house more than fifteen miles from Kampala, while she waited for the outcome of her final exams. Apolonia Lobo, a friend who was behind her at the Medical School, called to let her know the results had been released and she had passed. “Everyone on campus is looking for you. You’d better come quickly,” Prof. Namboze recalls Apolonia Lobo telling her.

“My fellow women students at the University, bubbling with excitement, walked from Makerere through Kampala to my parent’s home. There were no buses or taxis to Nsambya at the time,” she says.

“Apolonia was the only one who knew where I was and the telephone number. I had gone to a place where not even the media could find me. I immediately got a lift from my friends back to Mary Stuart Hall,” Prof. Namboze says. Then, she drove with her to Nsambya to inform her family.

“My fellow women students at the University bubbling with excitement walked from Makerere through Kampala to my parent’s home. There were no buses or taxis to Nsambya at the time,” she says. “I was glad I had not let them down. All of them were an important part of a revolution for the education of the girl child in East Africa.”

By the time they arrived at my parents’ home in Nsambya, word had spread fast like a wildfire, far and wide across Kampala, triggering jubilation. “When I joined University, many people in my village wondered whether I, a girl they had watched growing up, would make it. At that moment, though, they were in a frenzy having already heard the news,” she says.

Prof. Namboze further recalls; “several had already decorated both sides of the road leading to my parent’s home with banana trees, papyrus from the swamps and red bougainvillaea flowers, with a few white ones, and palm leaves as well. It was so colourful.”

And celebrations started instantly. “There was so much excitement, I have never seen the likes of it and don’t think I ever will. You cannot imagine what I saw! Later in the evening, my fellow women students walked back to Mary Stuart Hall. My achievement was theirs too. We had moved ahead,” she says.

At the time of the graduation ceremony, Prof. Namboze was doing an internship at Mulago Hospital. “We were trained both in Medicine and Surgery to work in settings with few resources, even if we were the only doctors available for miles around or in an entire district,” she says.

Prof. Namboze says each intern was assigned to a medical unit called a firm under the supervision of a Chief, either a professor or a Government specialist. First, she was assigned to Medicine under the supervision of Dr. Vesey, a British physician who worked for the government. After six months, she was assigned to Obstetrics and Gynaecology under Prof. C.W. Rendle-Short of the Medical School. Prof. Namboze says she had to work her way from Intern to Junior Houseman and then Senior Houseman, under supervision. After the internship, she was assigned to Pediatrics under Dr. Derrick Brian Jeliffe.

“The training involved long hours and very little sleep because the doctors were few, and the patients many,” she says. “It was quite tedious. You lost several pounds while at it but, came out seasoned. Interns took patient histories, conducted patient examinations and then made referrals to a Medical Officer, who was the immediate supervisor.”

Prof. Namboze says lab technicians were few and did not work outside normal hours meaning that at times intern doctors had to take blood tests, and do the blood grouping and cross-matching for patients that needed transfusions.

Receiving a degree from Queen Mother

The graduation ceremony held on 20th February 1959 was presided over by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother, who was the Chancellor of the University of London to which Makerere College was affiliated.

The Queen Mother mentioned Prof. Namboze in her speech, saying she was delighted that East Africa’s first woman doctor was graduating from Makerere. “I learn with particular interest that amongst those students whom I have just received is the first African woman to qualify as a doctor in East Africa,” said the Queen Mother.

She further described Prof. Namboze’s graduation as “the most memorable landmark in the purposes of this University College.” The Queen Mother expressed optimism that Prof. Namboze would be “first of many to profit by the opportunities which are steadily developing here, and that others will follow in her footsteps to spread healing and knowledge amongst their fellows.”

Prof. Namboze appeared in a memorable picture shaking the Queen Mother’s hand on graduation day. The picture was published in the London Times Newspaper on 24th February 1959.

The Uganda Argus of 21st February 1959 reported that “Namboze was heartily applauded as she left the dais” after a handshake with the Queen Mother.

For Prof. Namboze, graduation required dressing up appropriately. She sought advice from Prof. Margaret MacPherson, who was a lecturer at Makerere University for several decades and authored a book on the University’s history titled They Built for the Future: A Chronicle of Makerere University College 1922-1962. “I didn’t know what to wear when going to meet the Queen Mother. She advised me to wear a suit. I had to buy the material, take it to a tailor and have one made for me for the function” Prof. Namboze says.

The medical class of 1958 had eight students but only seven finalists, and only two graduates from Uganda. Prof. Namboze says on her graduation day, she did not see patients at the Hospital. “My mother attended the graduation ceremony, but my father, who was my greatest cheerleader, had gone to Britain for mid-career development and to upgrade his teaching skills,” she says.

“He knew the date of my graduation and saw my photograph, far though he was, four days later, on the front page of the London Times newspaper and probably showed it to all his tutors and classmates and anyone that cared to know. He would have enjoyed seeing everything live and hearing the applause,” Prof. Namboze says.

Months after Prof. Namboze graduated, her father returned and Sir Alexander Galloway and the Faculty of Medicine threw a special party to congratulate her in the gardens of the Dean’s residence, to which they invited her parents. “The Faculty presented me with a lovely gift that I still treasure,” she says. “The greatest gift they gave me, though, was the environment, conducive to learning, and a belief in my potential to make it.”

Edited by Colette Kiggundu

Get Involved

Are you a Member of Staff, Student Body, Alumni, General Public, or Well-wisher? Find out how you can get involved here, or share your Makerere experience with us.

Makerere

Makerere